Last Supper Metaphysics: The Causality of the Vine and the Branches

/by urban Hannon

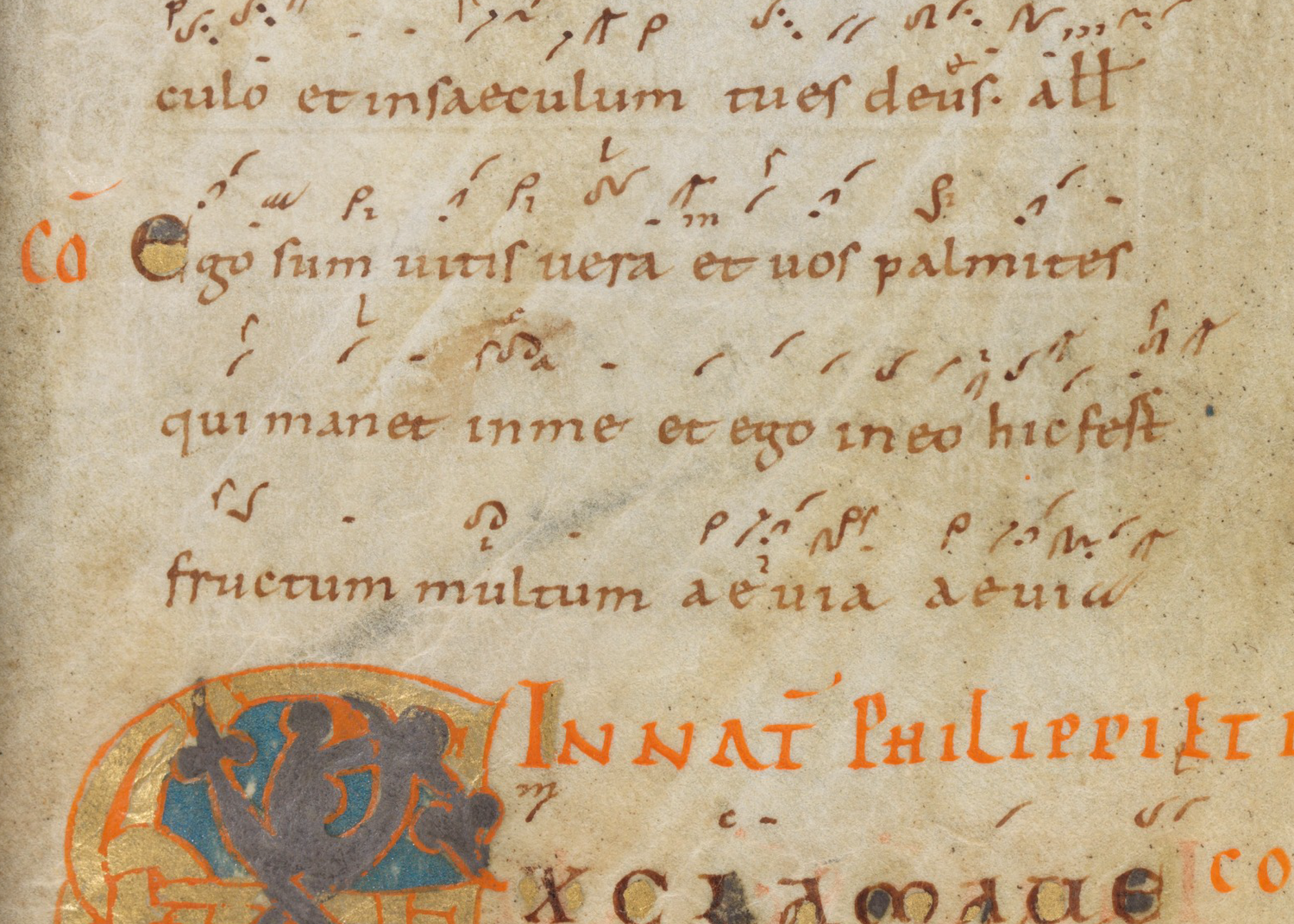

I am the vine; you are the branches. He who abides in me, and I in him, he it is that bears much fruit, for apart from me you can do nothing

—words of the Savior from the holy Gospel according to St. John…

OUR LORD played a great many different roles at the Last Supper. Inasmuch as he was celebrating a Passover seder, he was just another observant Jew—whereas foretelling his betrayal, he played the prophet, and offering sacrifice, the high priest. He was a parting friend to his apostles, raising one last farewell toast, and yet he also acted the bathing maid to their feet. So much did our Lord become all things to all men that evening that at one point he deigned to play a civil arbitrator, to settle the disciples’ petty dispute about who among them was the greatest. He even let the beloved John use him as a pillow. There is, however, one role which our Lord took upon himself on Holy Thursday night that we may not have noticed. And it is here, just between promising the Spirit and giving his new commandment, that Christ Jesus plays the most surprising character of all: a metaphysics professor.

I am the vine; you are the branches. Among other things, this is a metaphysics lecture: a lesson from the Son of God in what St. Thomas Aquinas will call first and second causes. God, the first cause, is the vine. We, the second causes, are its branches. It’s a simple metaphor—so simple that the proud theologians among us might assume that we’ve got it, without having paid the thing too much attention, and then move on to other more challenging matters which we deem somehow worthier of our ingenious disputations (“Grace/nature debate, anyone?”). I’m sure you philosophers are much more docile, but for anyone—philosopher or theologian—to pass over this too quickly would be a mistake, and a failure to take our Lord seriously as the Logos, as the Truth. Indeed, so good a teacher is Christ Jesus that with this one simple illustration of the vine and the branches, he has left to his Church the means to resolve some of the most important and difficult questions, both of nature and of grace, which he knew were to arise in the world before his triumphal return in glory. We will limit ourselves to four such questions here, in our own consideration of this Last Supper metaphysics: first, creation; second, causality; third, free will; and finally, cooperation with grace.

Let’s start “in the beginning”—that is, with the doctrine of creation. Now, there are some aspiring theists (including our friends the Hasidic Jews with their Kabbalistic mythology) who like to claim that, in order for the infinite God to have created anything other than himself, he first had to withdraw a bit of his infinity, so that he might make some room for creatures to come to be. That’s a problem, because in Christian terms that means that in order for God to be the Creator, he first had to stop being God. The trendy postmodernists would call this an “ontotheology,” which is a fancy name for what we used to call idolatry—but in either case, it’s just bad metaphysics, and the vine-branch imagery teaches us why. Our God’s infinity is not a material, spatial, imaginable infinity, by which he fills everything up and crowds anything else out. His is rather an infinity in being, and he does not need to retract that infinite being for us to come to be. On the contrary, it is only by participating in his infinite being that we can be at all.

I am the vine; you are the branches. A vine and a branch might both be called “beings,” but the “beings” of vine and branch should remind us of philosophy lesson one: “Being is said in many ways.” A vine is a complete substance unto itself, a living body with its own proper existence—but a branch is not. A branch exists, and so is a being, only insofar as it has some share in the primary being of the vine. Mutatis mutandis for creatures and the Creator: God and we are not “beings” in the same sense (God and we are not anything in the same sense). Pace the Hasidics, we do not exist at the same level of being as God, such that we could somehow displace him by our existence. If we should use the word “being” in the sense of a created being, therefore—a secondary, participated, dependent being—then God is not a “being” at all, but prior to all being as its determining principle or precondition (cf. the Neoplatonists—or, perhaps, Jean-Luc Marion). Whereas if we use the word “being” in the sense of the divine being in relation to its created effects—the primary, unparticipated, supereminent being—then this time it is the creatures which do not count as beings. Ergo our Lord’s revelation to St. Catherine of Siena: “Catherine, I am he who is; you are she who is not.”

We might put our question this way: Does a vine have to stop being a vine in order to sprout a branch? Certainly not. Nor is a branch any threat to the real and absolute primacy of the vine, for all that the branch is, it has from the vine. If anything, that branch gives even greater honor to the vine, by showing forth the power that was in the vine all along, as well as its generosity in this sharing of itself. Similarly, God’s creatures do not detract from his infinity; they manifest it. So much, then, for the problem of created being.

But what about our second problem, namely that of created action? For certain philosophers, the same difficulty repeats itself. They argue that, if God is really all-powerful and all-provident, then God himself must be the cause of everything (so far so good), and that therefore no created thing can be called a true cause at all (not so good). On this theory, that rock didn’t really crack your windshield—God did—the rock just gave him the occasion to step in and do so. Whence this philosophy is often referred to as occasionalism (and I’m thinking here in particular of a certain medieval Persian and an early-modern French Oratorian—“Who are Al-Ghazali and Malebranche?” for those playing along at home). Now, let’s give the devil his due: This sad occasionalist view of things would be right, if a creature’s action were supposed to be its own to the exclusion of being God’s: As the branch cannot bear fruit by itself, unless it abides in the vine, neither can you, unless you abide in me. But then, like our being, our activity is not ours-rather-than-God’s, but ours-as-a-share-in-God’s. For orthodox Christians, there’s no issue here, because just as all that we are comes from God, so also all that we effect comes from God. He who abides in me, and I in him, he it is that bears much fruit—and in this ontological sense that we’re considering here, all things abide in God: That is just what creation means.

The vine-branch-fruit triad really is a brilliant illustration of how this secondary causality works (good job, Jesus). It is not that the fruit is partially caused by the branch, and partially caused by the vine. Rather, the entire fruit is from the vine, and the entire fruit is from the branch. As effect, it owes its whole being to both—but in an order! The branch brings forth the fruit, but only by its being the branch of this vine. The vine, in other words, is the cause of the branch’s causing. And this is precisely how the first cause relates to a second cause: as the cause of the latter’s causality. The vine causes the branch causes the fruit. Creatures are real causes then, because God, in his higher causality, causes them to be such.

Some philosophers are willing to come with us this far, and admit that God really can create and that creatures really can be causes. But (and here is our third consideration) they stop short when they arrive at creatures who act with freedom. We might think here of that so-called “free will defense” for explaining away the problem of evil, which tries to get God off the hook for sin by putting the human will beyond the reach of his providential control. We might also think of Alasdair MacIntyre’s recent attempt to oppose determinism by making the ingenuity of human freedom to be surprising even to God. Suffice it to say: This view of freedom as being somehow outside of God’s causality is completely untenable on a vine-branches metaphysics. Apart from me you can do nothing, our Lord says, and (again good job, Jesus) he’s right. Freedom does not mean being uncaused by God. We have another name for that, and it’s “nonexistence.” God’s causality is so transcendent—like a vine to its branch, though infinitely more so—that just as God can cause a tree to be a real cause according to its own nutritive principle, and a fish according to its sensitive principle, so he can cause a man to act according to his own rational principle. And this is all we mean by freedom: to act rationally for an end determined by reason, rather than for one predetermined by nature. Nor does this make God responsible for man’s bad choices, because such moral evil is just the branch failing to bring forth its good fruit by choking itself off from the life from the vine—which, needless to say, is hardly the fault of the vine. If a man does not abide in me, … as a branch … [he] withers. It turns out that, although we branches need help to flourish, withering requires no outside cause whatsoever. This is St. Augustine’s constant refrain against the Manicheans: We don’t need to posit a first principle of evil, because failing is the one thing we can do all by ourselves.

Thus far, Christ’s Last Supper metaphysics applied to the order of nature—to created being, created action, and created freedom. At this point, I hope you’ll forgive me for going on a theological digression at our philosophical meeting, because my fourth consideration falls rather in the order of grace. Probably it goes without saying that the first meaning of I am the true vine is Christological, about Christ and our Christian life in him. But my theological interest today is more general than this, more a Prima Secundae problem than a Tertia Pars problem, grace as such rather than grace in relation to the God-man. If anything, here our Lord’s lecture on the causality of the vine and the branches has been even more needed than in the realm of philosophy, but no less neglected. Someone should cut a St. Patrick’s Bad Analogies-style video of the awful metaphors in circulation to explain what it means for a Christian man or woman to cooperate with God’s grace. One popular, sentimental image casts the Christian as a small child simply letting its Father carry it along a beach from here to heaven. Cue the Irish peasants: “That’s Quietism, Patrick.” “Yeah, come on, Patrick.” Whereas some sophisticated manuals of spiritual theology tell us that we first have to raise the sails on the boat of our soul, so that the wind of grace can come and move us. “But that’s semi-Pelagianism, Patrick.” “Yeah, come on, Patrick.” A high school teacher once taught me that God throws us the football, but then we have to run with it. “Pelagianism again, Patrick.” Whereas a seminary professor preferred God as the lead in a partner dance. “Quietism and Pelagianism, Patrick.” “That’s hard to do there, Patrick. If Jesus Christ Lord of the Dance is physically moving you while you’re standing limp then it’s Quietist, Patrick, but if you’re bringing in moves of your own to harmonize with his then you’re back to Pelagianism, Patrick.” “Wow, Patrick.” “Yeah, come on, Patrick.” You get the gist.

The problem isn’t that these common analogies limp; it’s that they can’t stand up to begin with. They’re misleading not at some further extrapolation, but at the very point for which they were employed in the first place: namely, to illustrate the relationship of cooperation between two radically unequal causes, me and God—in other words, to show how my cause and I can then cause something else together. Would that our spiritual theologians had turned to St. John’s Gospel. There they would not have found, “I am the true quarterback,” or, “I am the true piggyback-ride,” or, “I am the ballroom lead,” or, “I am the wind beneath your wings,” but I am the true vine. Christ gave us this Last Supper metaphysics, in no small part, to save us from such heresies. All of which heresies, notice, pit God and me against each other, as equal and opposite forces which necessarily exclude one another: Either God is doing the work, so I’m not, or else I’m doing some different work, bringing something new to the table which may complement God’s action but is not itself a part of it. This is nonsense. Grace perfects nature, and as we have seen, in the natural order I am a real cause, but only because God causes me to be. So also in grace: I am really cooperating, but only because God gives me to do so. I am the vine; you are the branches.

All of this is very speculative—which in a sense is just fine, not only because this is the ACPA, but also because practical truths are for the sake of speculative ones, not vice versa. But thankfully it happens that, when we get our metaphysics right, nothing is more useful than metaphysics. Indeed, how could the profundities of our Lord’s Last Supper discourse not deepen the virtues he has already infused into our souls? On the negative side, reflecting on our absolute dependence upon God, as branches upon the true vine, will increase our share in humility: Apart from me you can do nothing—and gratitude: What have you that you did not receive? On the positive side, our considering that the true vine, who is giving us this life and power, is none other than God himself, will strengthen our hope: If you abide in me, and my words abide in you, ask whatever you will, and it shall be done for you—and magnanimity: He who believes in me will also do the works that I do, and greater works than these; With God all things are possible.

Without God, we are nothing. With him, we are more than we can dream. We are God’s: apostrophe-s, or lowercase-g: We are gods. His divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness, says St. Peter, through the knowledge of him who called us to his own glory and excellence, by which he has granted to us his precious and very great promises, that through these you may … become partakers of the divine nature.

I am the vine; you are the branches. He who abides in me, and I in him, he it is that bears much fruit.